The nation’s gift

The Greek historian Herodotus observed that Egypt was the gift of the Nile and although it might now be a cliché, it also happens to be true. Ancient Egyptians called it simply iteru, the river. Without the Nile, Egypt as we know it would not exist.

The exact history is obscure, but many thousands of years ago the climate of North Africa changed dramatically. Patterns of rainfall also changed and Egypt, formerly a rich savannah, became increasingly dry. The social consequences were dramatic. People in this part of Africa lived as nomads, hunting, gathering and moving across the region with the seasons. But when their pastures turned to desert, there was only one place for them to go: the Nile.

Rainfall in east and central Africa ensured that the Nile in Egypt rose each summer; this happened some time towards the end of June in Aswan. The waters would reach their height around the Cairo area in September. In most years, this surge of water flooded the valley and left the countryside hidden. As the rains eased, the river level started to drop and water drained off the land, leaving behind a layer of rich silt washed down from the hills of Africa.

Egyptians learned that if they planted seed on this fertile land, they could grow a good crop. As more people settled along the valley, it became more important to make the best use of the annual floodwater, or there would not be enough food for the following year. A social order evolved to organise the workforce to make the most of this ‘gift’, an order that had farmers at the bottom, bureaucrats and governors in the middle and, at the top of this pyramid, the pharaoh.

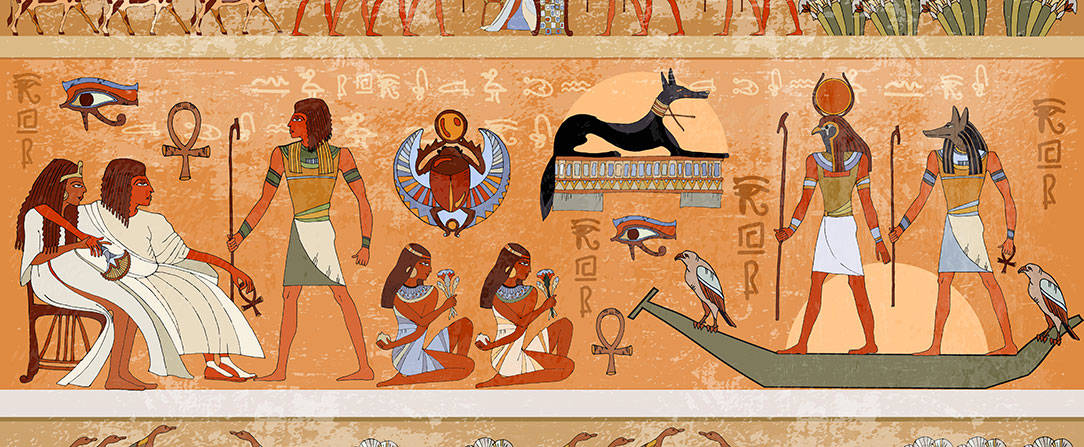

Egyptian legend credited all this social development to the good king Osiris, who, so the story went, taught Egyptians how to farm, how to make best use of the Nile and how to live a good, civil life. The myth harks back to an idealised past, but also ties in with what we know of the emergence of kingship: one of the earliest attributions of kingship, the pre-dynastic Scorpion Macehead, found in Hierakonpolis around 3000 BC, shows an irrigation ritual. Which suggests that even right back in early times, making use of the river’s gift was a key part of the role of the leader.

The rise of the Nile was a matter of continual wonder for ancient Egyptians, as it was right up to the 19th century, when European explorers settled the question of the source. There is no evidence that ancient Egyptians knew where this lifeline came from. In the absence of facts, they made up stories.

One of the least convincing of all Egyptian myths concerning the rise of the Nile places the river’s source in Aswan, beneath the First Cataract. From here, the story went, the river flowed north to the Mediterranean and south into Africa.

The river’s life-giving force was revered as a god, Hapy. He is an unusual deity in that, contrary to the usual slim outline of most gods, Hapy is usually portrayed as a pot-bellied man with hanging breasts and a headdress of papyrus. Hapy was celebrated at a feast each year when the Nile rose. In later images, he is often shown tying papyrus and lotus plants together, a reminder that the Nile bound people together.

But the most enduring and endearing of all Egyptian myths concerning the river is devoted to the figure of Isis, the mourning wife. Wherever the river originated, the annual rising of the Nile was explained as being tears shed by the mother goddess at the loss of the good king Osiris.

Matters of fact

Wherever it came from, the Nile was the beginning and end for most Egyptians. They were born beside it and had their first post-natal bath in its waters. It sustained them throughout their lives, made possible the vegetables in the fields, the chickens, cows, ducks and fish on their plates, and filled their drinking vessels when they were thirsty. When it was very hot or at the end of a day’s work, it was the Nile that provided relief, a place to bathe. Later, when they died, if they had the funds, their body would be taken along the river to the cult centre at Abydos. And it was water from the Nile that the embalmers used when they prepared the body for burial. But burial was a moment of total separation from this life-source for, if you were lucky, you were buried away from the damp, where the dry sands and rocks of the desert would preserve your remains throughout eternity.

But not everything about the river was generous for it also brought dangers in many forms: the crocodile, the sudden flood that washed away helpless children and brought the house down on your head, the diseases that thrived in water, and the creatures (among them the mosquito) that carried them. The river also brought the taxman, for it was on the level of flood that the level of tax was set. The formula was simple. Bureaucrats watched the rise of the river on Elephantine Island, where a gauge had been cut along the side of the rock. Each year’s flood was recorded at its height. If the water rose to the level of 14 cubits, there would be enough food to go around. If it rose to 16, there would be an abundance – and abundance meant good taxation. And if there were, say, only eight cubits, then it was time to prepare for the worst because famine would come and many would follow Osiris to the land of spirits beyond the valley.

The river also dictated the rhythm of life and everything started with the beginning of the inundation: New Year fell as the water’s rose. This was a time of celebration and also, for some, of relaxation for as the land was covered with water and one needed a boat to travel from one village to the next, farmers found time to catch up on long-neglected chores, fixing tools and working on their houses. This was also the period of the corveé, the labour system by which it is thought many civic projects were built, among them the pyramids, the canal cut through from the Nile to the Red Sea and, in the 19th century, the Suez Canal.

Spices International Travel Group

Spices International Travel Group